A Rousing Fiddler at Toby’s Columbia

Posted on BroadwayWorld.com on February 20, 2013

Fiddler on the Roof was a monster hit when it premiered in 1964, surviving for 3,242 performances and appearing on three different stages. It has since had four Broadway revivals, and has been revived constantly at every level from summer camps to high schools to community theaters. Virtually every theatergoer has seen the show multiple times. Which is why, for instance, in the musical The Last 5 Years, the heroine can sing mournfully about appearing in summer rep in Ohio with “a midget … playing Tevye and Porgy.” No introduction or explanations necessary. Universal familiarity can be safely assumed.

Any new revival therefore prompts two meditations: a) What’s the reason we keep needing a Tevye fix? and b) What’s special about this one (this one for the moment being a first-rate production at Toby’s in Columbia)? That I cannot tell you in one word. It takes a few.

When you stop and think about it, this is a very peculiar kind of crowd-pleaser. Yes, at its heart is a tale about family love, and that is a nice and reassuring topic. But the family and its love are set against a community that is disintegrating in response to pressures both from within and without. This disintegration is not the benign kind that naturally occurs as each generation succeeds the next (even if that kind is limned in the song SUNRISE, SUNSET). This is a crumbling of community mores surrounding courtship and parental prerogatives, and a crumbling of the uneasy place that Russia had crafted for its Jewish populace, all set against the crumbling of imperial Russia. The final action in the play is the literal emptying out of the town and the disintegration of the community as its inhabitants enter a new diaspora. Every shtetl-dweller exiting the stage at the end is coping with sadness and loss. This doesn’t seem much like theatrical comfort food.

It wouldn’t have helped, in 1964, that lots of children of that new diaspora would have been sitting right in the audience. Indeed, when I saw the original Broadway production, I was sitting with my father, a man whose own father had left a Lithuanian town very like Anatevka shortly before the 1905 action of Fiddler. And that original audience, by and large, would have had a very different take from that of the characters on both the family’s story (Tevye’s successive failures to determine the marriages of three of his daughters) and the community’s (fracturing in the face of official governmental anti-Semitism). Growing up, I knew many members of that generation, and not one of them would have approved of the old courtship rituals that Tevye, his wife Golde, and Yente the official village matchmaker, try and fail to enforce, and not one would have looked at leaving Anatevka and arriving in America as anything other than a great blessing. The task and, let us say, the achievement of Fiddler, then, was to make its audiences feel that something had after all been lost in that transition.

But for the kind of universal appeal that Fiddler achieved, even more was required. It is not simply the Ur-story of one segment of the American Jewish community; it has resonance for everyone in a nation of immigrants. All of us are glad we’re here (well, almost everyone; cf. the song AMERICA in West Side Story), but it may take some educating to remember that some kind of price was paid to get us here. This is the story of that price. And maybe the lift one gets despite that sad parade of Anatevkans trudging offstage at the final curtain is that we know, though they cannot yet know as we do, that the price was worth it. Getting the heck out of Anatevka or Dublin or Calabria or wherever we came from, we were freed both from governmental oppression and also from the dead weight of all that Tradition that Tevye so values, though he proves unable to live up to it. Tevye is right, of course, that Tradition played a great role in stabilizing the communities our parents came from. But the children of that community, in 1964, would ordinarily have added “Good riddance” to that thought. So Fiddler traffics in the safest kind of nostalgia, reminiscences of a world no one would want to return to. It’s a lovely flirtation with a way of life that is safely dead.

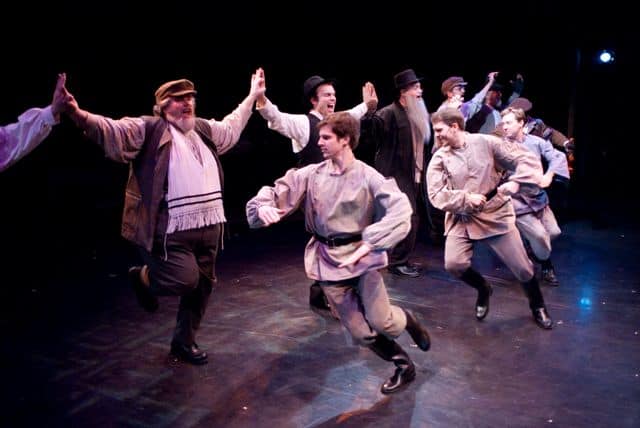

Naturally, none of that would have mattered, had the songs not been so infernally catchy, the dancing not so athletic and exotic, the sentimentality not so powerfully schmaltzy, and the love-stories, even perfunctorily sketched, not so appealing.

That’s my take on the first question. As to the second, it goes without saying that no one goes to see Fiddler for originality of staging, performance, costume, or anything else. Everyone on either side of the footlights knows how it should be done. The only real question is whether it is done well. And I’m pleased to say that it’s done very well by Toby’s.

In fact, I can go further. Over the years, I’ve seen a number of shows on Toby’s two stages. Toby Orenstein has assembled what amounts to a repertory company in the past three decades. They are nimble, adaptable, and they obviously know each other’s moves. She has deep depth on her bench. When you have a group like that, you can get a lot out of them. This is the best ensemble effort I’ve personally observed from this crew. Not a false move in the bunch.

Tevye is portrayed by David Bosley-Reynolds, a big man more in the Topol than the Zero Mostel mode, most recently seen by this reviewer at Toby’s as the King of Siam. As our point-of-view character, he is drawn with greater depth than are most of his compeers, and we must believe that he is discovering the thoughts in his speeches and songs for the first time. There are only a certain number of possible readings of Tevye’s words, but Bosley-Reynolds manages to make it new as possible. The other major roles: Golde (Jane C. Boyle), Tzeitel (Tina Marie DeSimone), Hodel (Debra Buonaccorsi), Yente (Susan Porter), Motel (David James), Perchick (Shawn Kettering), Lazar Wolf (Andrew Horn), Chava (Katie Heibreder) and Fydeka (Jeffrey Shankle) are beautifully acted, sung and danced. (DeSimone and James also choreograph and direct.)

There is also something about the show that works especially well with a theater-in-the-square format, like the Toby’s Columbia stage. Frequently the principals are isolated in the midst of a great deal of choral movement and dancing, and being so close to the action allows the audience to focus without being distracted. Even the sound system, sometimes a bit dodgy at this venue, seems to have given up fighting audience comprehension for this production.

In short, while no one ever needs an excuse, exactly, to revive Fiddler again, a rousing performance certainly justifies it more. This is one rousing performance.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for graphic

I lived in London and Vienna before coming to the United States, and grew up mainly in Ann Arbor. I was writing plays and stories as early as grade school. My undergraduate years at the University of Pennsylvania, where I first reviewed theater, for the college paper, were succeeded by graduate study at the Johns Hopkins University, where I earned a doctorate in English Literature.

I lived in London and Vienna before coming to the United States, and grew up mainly in Ann Arbor. I was writing plays and stories as early as grade school. My undergraduate years at the University of Pennsylvania, where I first reviewed theater, for the college paper, were succeeded by graduate study at the Johns Hopkins University, where I earned a doctorate in English Literature.