Just the Songs (and Dance), Ma’am: SMOKEY JOE’S CAFE at Toby’s

Posted on BroadwayWorld January 31, 2012

Once upon a time, musicals were collections of what the producers hoped would become hit songs, held together with a thin if sparkly integument of dance, plot and dialogue. Artists like Cole Porter and Dorothy Fields wrote shows like that. Then Rodgers and Hammerstein dragged the whole thing to a different level, the so-called “book show,” in which everything (music, song, and dance) was integrated into a dramatic whole.

There were those who felt this was not an unmixed blessing, both because (let’s face it) there aren’t enough Rodgers and Hammersteins and Stephen Sondheims to go around and because big hit songs may have something to offer the stage even when they aren’t transformative soliloquies. Finally, starting in the 1970s, came the counterrevolution, the “jukebox musical,” which would string together a bunch of preexisting hits, with or without plot or dialogue.

The Leiber & Stoller Oeuvre

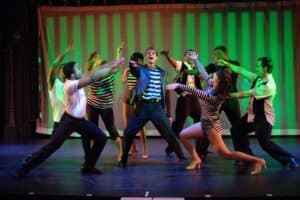

The songbook of Jerry Leiber (1933-2011) and Mike Stoller (1933- ) is a natural for jukebox musical treatment, because it encompasses such variety that it requires little by way of setting to stay interesting. You don’t need a plot, you don’t need performers to talk or act, all you need is a band, some choreography and costumes, and some great singer/dancers, and you’re there. And that is the formula for Smokey Joe’s Café, holding forth for a while at Toby’s Baltimore.

This confection, which premiered on Broadway in 1995, showcases a good deal, though by no means all, of the Leiber-Stoller variety: torch songs, rock-n-roll, power pop, soul, novelty numbers, even touches of country. With a crew of ten talented performers whose only job is to put the songs across and dance, the concept is simple. Smokey Joe never was a big hit with critics, who tended to feel that the songs could have been served better by showing them in period context (something attempted for the girl group oeuvre, for instance, by Beehive, seen last year at Toby’s). Audiences begged to differ, though, giving the Broadway incarnation five years and over 2000 performances.

Neighborhood from Two Vantagepoints

Whether you agree with the critics or with the audiences is a matter of individual taste, but if you like it, you will do so despite the sketchy framing. For instance, sometimes two numbers will constitute a whole theme, e.g. TREAT ME NICE, where an importunate man (here Bryan Daniels) seeks acceptance from a hostile woman (Mary Searcy), and then she makes clear her continuing rejection of him by singing HOUND DOG. There’s a sort of cabaret going at the beginning of the second act, with the band’s platform thrust out from behind a scrim into the action, but it doesn’t affect the feel of the show much, for better or for worse. And there’s a song, NEIGHBORHOOD, that is sung at the beginning, middle and end, as a framing device, with a reference to snapshots of a bygone time – but as the show isn’t about bygone times or individual memories or even recognizable places, it lends no obvious structure to the show.

Then again, NEIGHBORHOOD is also a case in point on the other side of the argument. If you never heard of this 1974 number, join the crowd; you can’t even download the original on iTunes or Amazon, which tells you all you need to know about how much of a nonevent in the Leiber/Stoller canon it was – in the context the critics were crying out for. But forgetting context, NEIGHBORHOOD somehow turns out to be a flat-out gorgeous ballad that cries out for a choral setting, such as the show properly gives it. I was perfectly okay with hearing it three times, just as I was perfectly okay with most of the other things about the show.

Made of Rubber

I loved the dancing and clowning of Bryan Daniels, whose joints, to all appearances, are made of rubber (as is his face). Mary Searcy and Debra Bunoaccorsi were sultry throughout, but particularly in a quasi-burlesque rendition of an Elvis Presley number, TROUBLE. The tight choral singing of the men (e.g. RUBY BABY) and the women (WOMAN) was impressive. And the list of songs you know and would love to hear again (POISON IVY, ON BROADWAY, THERE GOES MY BABY, LOVE POTION #9, SPANISH HARLEM, STAND BY ME) and some worthwhile ones you’ve never heard of (like the aforementioned NEIGHBORHOOD) is long. The pit band led by Cedric Lyles, whether in front of or behind the scrim, is a pleasure. And you cannot fault the snappy choreography of Ashleigh King and Anwar Thomas.

In short, it’s all about the songs and the dance. If those things, standing unpretentiously by themselves, float your boat, then you’ll have a wonderful time. If you feel you need more (for example some insight into the state of popular culture in a bygone era when a small group of mostly Jewish composers and writers were writing most of the big crossover hits for black singers and bands – and that’s only one instance of all the possible areas the show doesn’t get into) then you won’t.

The audience I was watching with did. And so did I. Sometimes all that drama stuff and all that highfallutin’ context just makes you think too hard, and you want just the song and the dance, ma’am. At times like that, Smokey Joe’s Café, boasting 40 songs by two of the rock era’s finest tunesmiths, will do you.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn except for image

I lived in London and Vienna before coming to the United States, and grew up mainly in Ann Arbor. I was writing plays and stories as early as grade school. My undergraduate years at the University of Pennsylvania, where I first reviewed theater, for the college paper, were succeeded by graduate study at the Johns Hopkins University, where I earned a doctorate in English Literature.

I lived in London and Vienna before coming to the United States, and grew up mainly in Ann Arbor. I was writing plays and stories as early as grade school. My undergraduate years at the University of Pennsylvania, where I first reviewed theater, for the college paper, were succeeded by graduate study at the Johns Hopkins University, where I earned a doctorate in English Literature.