AS YOU Don’t LIKE IT: Misdirected Direction at Center Stage

Posted on BroadwayWorld.com January 30, 2016

It’s hard to imagine exactly what a completely realized version of Shakespeare’s vision in As You Like It (now presented at Center Stage) would look like. The gender stuff is so hard to think through. But directors and critics must each try.

It’s hard to imagine exactly what a completely realized version of Shakespeare’s vision in As You Like It (now presented at Center Stage) would look like. The gender stuff is so hard to think through. But directors and critics must each try.

Women to Men, Not the Other Way Around

One thing we know is that in this, as in at least two other comedies, female characters dress up as male and successfully assume not merely a different gender role, but different identities. Whether we are considering Portia in The Merchant of Venice or Viola in Twelfth Night or Rosalind in As You Like It, we are looking at women who have pulled off a successful imposture both as male and as some other character.

Considering that Shakespeare had only male performers to work with, it is not surprising that he almost always went in this direction; the only male Shakespearean character who passed himself off as a woman that I can recall was Falstaff in The Merry Wives of Windsor. And the explanation, I think, was that a male actor can be convincingly male, and as for the female role the actor also had to play, well, at least the performer would be no less convincing to Shakespeare’s audience than every other male “actress.” In other words, I think the intent was that the character’s maleness – and hence the character’s deception of the other characters while occupying a male role – carry great verisimilitude. That is important, because in not one of these plays is the imposture ever seen through. Everyone is fooled. The plots don’t work unless everyone is fooled. And the more plausibly the better, even in fanciful works like these plays.

At the same time, I think the great romance that every one of these female characters is involved in was envisioned as quite specifically heterosexual. Yes, I know, Shakespeare and his contemporaries may have lacked a vocabulary for homosexuality, but I see no inarticulate gay passions lurking beneath the surface of these comedies – at least not between female characters. (Maybe the male Antonio and the male Bassanio in The Merchant of Venice may have had a thing for each other, likewise maybe Achilles and Patroclus in Troilus and Cressida. But I can think of no female comparators.)

Not What Shakespeare Had in Mind

If these speculations about the “transvestite comedies” are correct, then what Center Stage is presenting, via an all-female cast, is far off from Shakespeare’s intention. There is simply no way that an average female performer can convey convincing maleness, either in a character who is supposed to be a man or a character who is supposed to be a woman pretending to be a man; primary and secondary sexual characteristics are hard to overcome. Instead, it becomes simply a stage convention that the disguises somehow work and that the other characters whom the disguises fool are not dolts for having been fooled. In the modern world, where female performers generally play the female roles, that convention must be the standard, even though it belies the gender dynamics Shakespeare probably had in mind.

But then we come to something Shakespeare probably never dreamed of: female performers taking on the roles of the male characters. It is complicated, because in our society a woman’s presentation as mannish is apt to be associated with homosexuality. (Yes, yes, of course there are plenty of exceptions, but the stereotypes are there.) If the heterosexuality of the romances that I believe Shakespeare wanted is to be realized with an all-female cast, there arises a real difficulty in how to present the male characters: too butch and the story takes on lesbian overtones, not butch enough and the maleness of the characters becomes as much a matter of mere convention as the convincingness of the transvestite disguises.

Assuming I have correctly identified Shakespeare’s vision, there is no perfect way to realize it, at least not on stage with flesh-and-blood performers unaltered by digital wizardry. But employing an all-female cast is apt to be among the less successful ways, for the reasons I’ve just touched on.

Or in the Alternative

In the alternative, you can say the hell with realizing Shakespeare’s vision, and simply have fun with your own. And that, I think, is the approach that director Wendy C. Goldberg has chosen to pursue at Center Stage. Going against Shakespeare’s grain may be a strange way to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, which is what Center Stage is claiming to do, but there is no denying that this version is often fun, if maybe not as much fun as Goldberg thinks.

It’s not simply that this show goes against the grain. At times it seems like outright rebellion against the Bard. This starts with various alterations of Shakespeare’s language to make it more accessible. The program tells us that it was “adapted by Gavin Witt,” Center Stage’s Associate Director and dramaturge. It was definitely adapted. For instance Charles the wrestler (Liz Daingerfield) tell Oliver, the hero’s evil older brother (Tia Shearer): “Tomorrow, sir, I wrestle for my credit.” Except that isn’t what Oliver says. Goldberg and Witt presumably fear for the comprehensibility of this line, and render it: “Tomorrow, sir, I wrestle for my reputation.” Okay, little harm done by one change, but there are a lot of emendations of this sort. It ends up being maybe more comprehensible, but not quite the play Shakespeare wrote. A big emendation is the removal of the Duke Senior (Margaret Daly) from the encounter of the forest exiles with the starving old man Adam – presumably for no other reason than that Adam is also portrayed by Margaret Daly. But in making that particular doubling choice, one of the most pleasing scenes is lost. Doing it Shakespeare’s way, we would have gotten a much fuller picture of the humaneness of Duke Senior’s encampment in exile, seeing the Duke, one old dude, taking pity on and providing care for an even older dude.

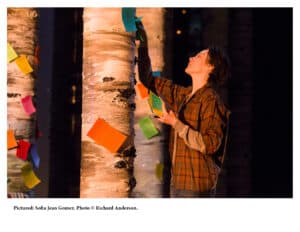

Back to the wrestling match: it stops being a wrestling match and turns into a choose-your-weapons-from-the-pile free-for-all apparently cribbed from Hunger Games, and Orlando, the hero, wins not by wrestling but by garroting Charles. That’s not even fun; that’s kind of creepy. And while we’re on the subject of Orlando, Sofia Jean Gomez,pictured above, presents him not as a handsome young man but as a butch young woman. Even for a female performer, there is a difference. So apparently Goldberg is messing with Shakespeare’s heteronormativity as well. And so it goes.

It’s a quite rational response to everything I’ve just said that the very title of the play suggests an ad lib, free-spirited approach – and that the impossibility of fully realizing Shakespeare’s vision makes some ad lib-ery de rigeur. And I guess the question in reply is whether it is wise to take up Shakespeare on his invitation to innovate wildly, if such an invitation there truly be.

To draw the obvious comparison, it is traditional to take liberties with Gilbert and Sullivan’s texts, subbing in contemporary references to take the place of, for instance, older political and cultural jokes whose context may have faded. And it is traditional to restage Shakespeare in settings different in time and place from those Shakespeare had in mind. But it is not so traditional to change Shakespeare’s language as we do Gilbert and Sullivan’s, even when Shakespeare’s lines are at their most archaic, or to cut out parts of scenes. It isn’t traditional because Shakespeare was a great poet, a great character-developer, and a great plot-spinner. Few of us can improve much on what he wrought. Some invitations may better be declined.

Ad-Libery

In fact, it is fair to say that the innovations that work best in this production are in keeping with “different settings” kind of innovations that are more traditional. The set (Arnulfo Maldonado) and the costumes (Anne Kennedy) are most effective. As Maldonado indicates in an interview in the program, his primary aim was to design a contrast between the dreadful world of Duke Frederick’s court and the delightful world of Duke Senior’s exile in the Forest of Arden. The straight and hard lines of the court on the one hand, and the curvy and tree-filled space of Arden together with a couple of delightful surprises on the other, come from different fictive universes, for sure. And it is a great change when the severely black-clad courtiers yield to exiles clad in some unimaginable but amusing cross between L.L. Bean and hippiedom.

I should also say a word in appreciation of the music and dance of the show. As You Like It is surely one of Shakespeare’s more musical plays, and I was quite taken by both of the approaches on display here. One is a percussive electronica for various dance routines which were appropriately angular and faintly military at the court, and which were more like folk-dances in the country. The other was, in effect, singing around the campfire accompanied by a beat box. I don’t believe I’ve ever seen a production of this show in which the songs were sung, even partly, by choruses, and it’s dramatic and pleasing here. Heather Christian (music director) and Karma Camp (choreographer) are to be commended.

The acting is Center Stage quality, which is to say excellent. I particularly liked Tracey Farrar as Amiens, the loose-limbed, beat box-equipped character who leads most of the singing; Celeste Den, who doubled in the very diverse roles of the usurping Duke Frederick, one of Shakespeare’s nastiest characters, and Corin the contented shepherd, and convinced me totally in both; and Angela Reed as Jacques, whose “seven ages of man” speech was beautifully served up. I also liked Jenna Rossman as Phebe, the scornful contemnor of her suitor Silvius until Rosalind sets her straight. She manages to make Phebe almost a pitiable character without sacrificing her mean streak.

You’ll note that I have singled out more the performers in the secondary roles; the reason I have not named the principals is that I really feel the strategic choices of the direction did not serve them well.

The production as a whole is served well by the venue, the Mainstage Theatre at Towson University’s Center for the Arts. It’s not quite as elegant as Center Stage’s regular house, which is under thorough renovation, for instance the floors beneath the seats are of concrete. But then again there is far more foot-room than Center Stage audiences generally get to enjoy. Overall, it’s a good, well-equipped house. I look forward to seeing Center Stage’s next show there as well.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn, except for production photograph

I lived in London and Vienna before coming to the United States, and grew up mainly in Ann Arbor. I was writing plays and stories as early as grade school. My undergraduate years at the University of Pennsylvania, where I first reviewed theater, for the college paper, were succeeded by graduate study at the Johns Hopkins University, where I earned a doctorate in English Literature.

I lived in London and Vienna before coming to the United States, and grew up mainly in Ann Arbor. I was writing plays and stories as early as grade school. My undergraduate years at the University of Pennsylvania, where I first reviewed theater, for the college paper, were succeeded by graduate study at the Johns Hopkins University, where I earned a doctorate in English Literature.