Truth Transcending Mere Facts: I AM MY OWN WIFE at The REP

Posted on BroadwayWorld November 4, 2013

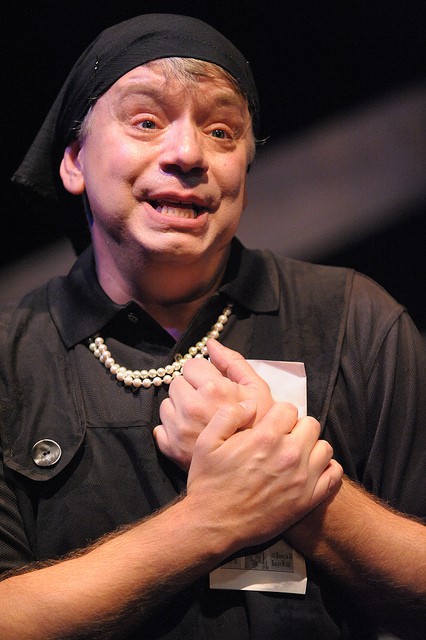

A one-man show, it is a tour-de-force for both the playwright, who appears as a character confronting the issues he wants his audience to consider, and the play’s solo performer, called upon to play between thirty and forty roles. I am speaking, of course, of Doug Wright’s I Am My Own Wife, the 2004 Tony Award-winner for Best Play, now in perhaps its third Maryland revival at the REP in Columbia, with Michael Stebbins, holding down the Walt Whitmanesque job of containing multitudes.

Briefly, the play recounts two stories. One is that of Charlotte von Mahlsdorf, transvestite, antiquarian, and curator of a museum preserving, among other things, memorabilia of Berlin’s homosexual underground from the Nazi era through the Communist one. The other is that of Wright, who interviews von Mahlsdorf, becomes her partisan while trying to build a play around those interviews, and then is forced to confront his subject’s unreliability as a witness to her own history, and the feet of clay she may be concealing.

It is the genius of the play that by the end, the audience may (although it is not compelled to) forgive von Mahlsdorf’s dishonesty, and even her treachery in betraying a friend and perhaps lover to the notorious Stasi (the East German secret police). If she really did that, we understand why; if she didn’t do it, and outsmarted the Stasi, which is the way she tells it, we understand that too. Either way, Wright the character and Wright the playwright conclude, and we are meant to conclude as well, there is something admirable about her steadfastness, her sheer endurance, in being the preserver and curator of a unique and priceless collection, the last woman standing, as it were.

This is no minor accomplishment for performer or playwright. I could better appreciate this accomplishment in light of having within the previous two weeks seen a play that tackled many of the same issues, and did it so much less effectively, Centerstage’s rendering of Marcus Gardley’s dance of the holy ghosts, also reviewed in these pages. There, as here, the playwright appears as a younger character confronting a somewhat inexplicable older figure. Both plays beg the question what makes the older character tick. In both plays it’s a dramatically urgent question: Gardley’s alter ego wants to see something of himself in his grandfather so he can establish a sense of connection with his own roots, while Wright, as a young gay man raised in a freer, more open era, still wants to tip his hat to a worthy predecessor. Gardley’s play never comes close to giving us a key to his grandfather’s unpleasant character; Wright’s wisely achieves the opposite extreme, giving us not one, but multiple plausible versions. Even when Wright and others confront Charlotte with a documentary record that seems to give some of her stories the lie, Charlotte comes back with a believable and sympathetic back-story that seems to trump the lie.

Gardley calls his show “a play on memory,” obviously laying claim to Tennessee Williams’ label of “memory play,” i.e. one in which the dramatic truth comes out even if the literal truth is somewhat obscured and contradicted by the swirling mists of memory. But Gardley doesn’t deliver, because there isn’t much truth there, just the absence of an explanation for abandonment. Wright does deliver, plentifully. In the end, the point of von Mahlsdorf was that she survived, and in doing so permitted her collection and the world it evoked to survive as well. As she tells the audience at the end: “You must save everything and you must show it as is. It is a record of life.” Everything, in this case, including accounts that cannot entirely be reconciled with the documentary history. It is all, in some sense, true, all, in some sense, a record of life.

This is my first experience of the play, so I have nothing to compare it, and especially Stebbins’ performance, to. But I can tell you that I was blown away by Stebbins’ ability to convey so many different voices, so many different personalities, mostly without the aid of changes of costume or makeup. I’ve had occasion in these pages to compliment dialogue/vocal coach Nancy Krebs before, and it’s time do it again, since she obviously had a hand in the shaping Stebbins’ versatility. The set, by Elizabeth Jenkins McFadden, struck me as a little sparse for a play in which descriptions of the sensual qualities of furniture played such a large role. But again, I have little to compare it to. Jay Herzog’s lighting design was imaginative and resourceful. And the direction, by local fixture Tony Tsendeas, seemed surefooted enough, though in a single-performer production it is difficult to determine where one participant’s contribution ends and another’s begins.

This production is a keeper. Unfortunately, it can’t be kept, with only two more weeks of performances. See it while there’s time.

Copyright (c) Jack L. B. Gohn except for production photo

I lived in London and Vienna before coming to the United States, and grew up mainly in Ann Arbor. I was writing plays and stories as early as grade school. My undergraduate years at the University of Pennsylvania, where I first reviewed theater, for the college paper, were succeeded by graduate study at the Johns Hopkins University, where I earned a doctorate in English Literature.

I lived in London and Vienna before coming to the United States, and grew up mainly in Ann Arbor. I was writing plays and stories as early as grade school. My undergraduate years at the University of Pennsylvania, where I first reviewed theater, for the college paper, were succeeded by graduate study at the Johns Hopkins University, where I earned a doctorate in English Literature.